Development of environmentally sustainable infrastructure through water conservation

The issue of water has become a global concern, especially in transboundary river basins. For example, Ethiopia, Sudan, and Egypt have been disputing for decades over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam on the Nile. In South and East Asia, conflicts have emerged over the sources of the Brahmaputra and Mekong rivers, which originate in Tibet. Such conflicts arise not from water scarcity itself, but from the absence of mechanisms for joint and fair water management.

Central Asia is among the most vulnerable regions in terms of “political water”. Two main rivers — the Syr Darya and the Amu Darya — serve millions of people across five countries: Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan. The resources of these rivers are formed in the Tien Shan and Pamir mountains (in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan), but the main consumers of water are the agricultural sectors of Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan. Thus, some countries control the sources, while others depend on the downstream flow.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the centralized water management system ceased to exist. The upstream countries (Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan) began constructing hydropower plants to ensure their own energy supply, especially in winter. However, this disrupts water availability for the downstream countries during the vegetation period, when irrigation is most needed. In turn, the downstream countries, which require water in the summer, are not always willing to finance or supply fuel to the upstream countries during the winter. As a result, contradictions arise almost every year, particularly during drought seasons.

Kazakhstan finds itself in a relatively vulnerable position. Its water resources come from seven transboundary rivers, including the Syr Darya, Ili, Irtysh, and Ural. Moreover, a significant portion of the runoff is formed outside the country — in China, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan. This makes Kazakhstan dependent on the decisions of its neighbors, especially amid climate change and growing water consumption in the region.

The situation with China’s active development of water resources in the Ili and Irtysh river basins causes particular concern. The construction of reservoirs and canals there may reduce the inflow to Lake Balkhash, the largest lake in southeastern Kazakhstan. In an unfavorable scenario, the region could face a new ecological disaster similar to the drying up of the Aral Sea.

Development of environmentally sustainable infrastructure

One of the most tragic examples of an environmental disaster related to water resources is the drying up of the Aral Sea. This is not only a symbol of the loss of a unique ecosystem but also clear evidence of the consequences of inefficient water resource management. In the mid-20th century, the Aral Sea was the fourth largest inland sea on the planet, and its shores were a region of active fishing, a stable climate, and economic prosperity. However, the massive diversion of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers for irrigation needs led to the rapid retreat of the sea.

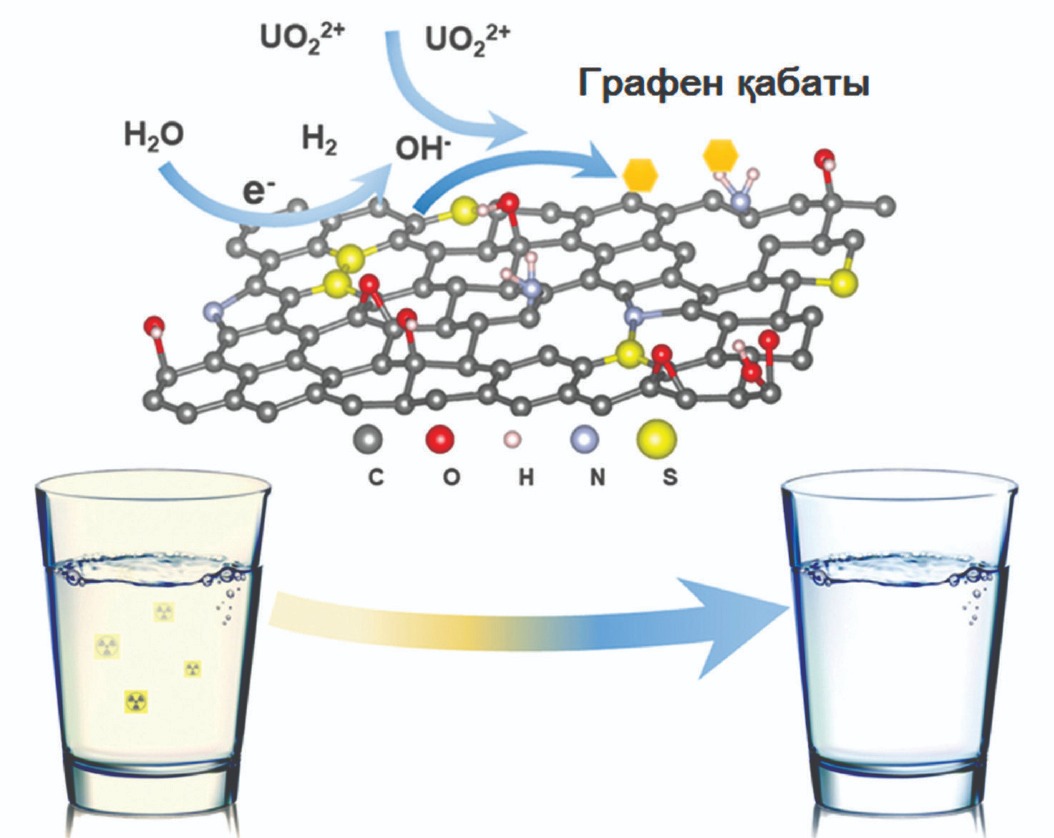

Today, much of its former seabed has turned into a salty desert — the Aralkum — with extremely low biodiversity, frequent dust storms, and severe health impacts on local populations. Experts warn that by 2040, the country — particularly the southern and central regions, where pressure on resources has already exceeded safe limits — may face an acute water shortage. Against this backdrop of challenges, the need to introduce innovative and environmentally sustainable solutions in the field of water supply becomes evident. It is precisely here that technologies such as graphene membranes for desalination and water purification can play a crucial role.

These technologies can not only make efficient use of alternative water sources — such as seawater and contaminated groundwater — but also provide high-quality filtration with low energy and economic costs. Moreover, if such technologies are based on processing local biomass, such as agricultural waste, they can generate additional environmental and social value — from recycling waste to creating jobs in rural areas.

What is graphene and why is it important?

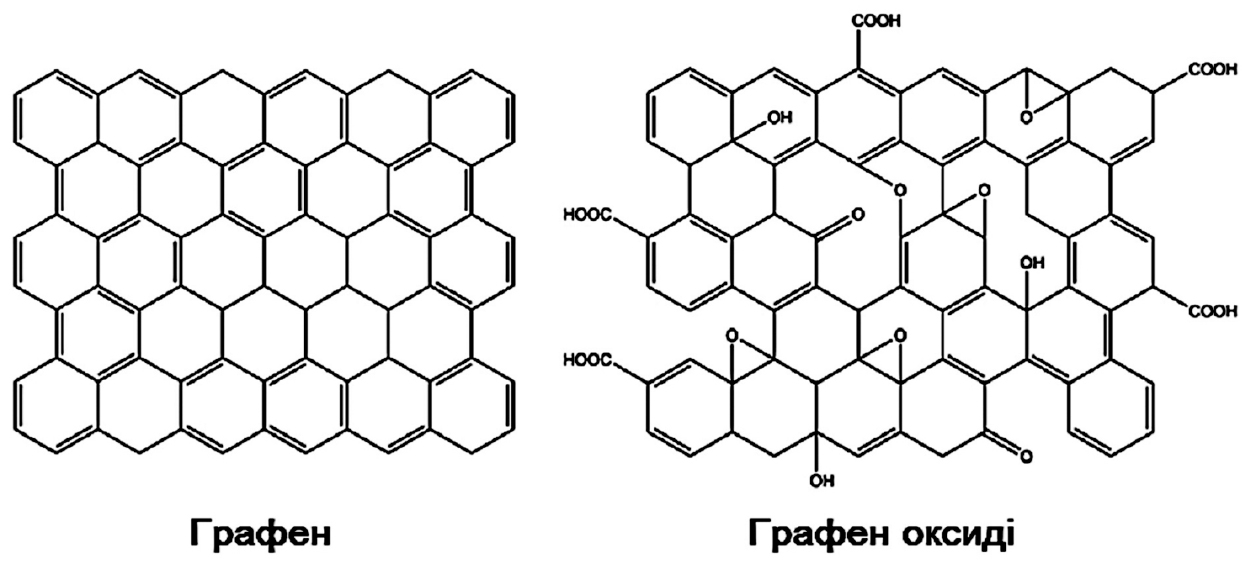

Graphene is a two-dimensional structure consisting of a single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal lattice. Due to its unique combination of properties — high thermal conductivity, flexibility, and molecular selectivity — graphene is considered one of the most promising materials of the 21st century.

Graphene is important because it combines characteristics that no other material has ever demonstrated. It is extraordinarily strong — hundreds of times stronger than steel — yet almost weightless and virtually transparent. Graphene conducts electricity and heat exceptionally well, making it a perfect candidate for use in electronics, batteries, flexible displays, and sensors. Its single-atom-thick structure allows the creation of ultra-thin and highly sensitive devices.

Furthermore, graphene has an exceptional ability to filter water: it can retain salts and pollutants while allowing only water molecules to pass through, opening new prospects for desalination and wastewater purification. It is especially valuable because graphene can be produced from biomass sources such as rice husks, wood, or food waste — making it not only highly efficient but also environmentally sustainable. All of this makes graphene a material of the future — capable of fundamentally transforming technology, making it cleaner, smarter, and more efficient.

My research focuses on developing an innovative technology for desalination of seawater and freshwater using graphene derived from rice husks — a by-product of the agricultural industry.

What is the essence of the method?

Today, graphene obtained from biomass represents an environmentally friendly and affordable raw material. While graphene production used to be an expensive and energy-intensive process, in recent years more sustainable methods have been developed that allow synthesis of the material from carbon-containing waste such as sawdust, rice husks, corn granules, coffee grounds, and even food residues. This approach not only reduces production costs but also helps solve the problem of utilizing agricultural and household waste.

The process of obtaining graphene from biomass involves the thermal decomposition of the raw material at high temperatures in the absence of oxygen (pyrolysis), followed by chemical or thermal activation to increase surface area, and then exfoliation of the resulting carbon material into thin graphene sheets. The result is a functional material with high specific surface area and porosity, capable of efficiently interacting with aqueous solutions.

The advantages of this method include not only the recycling of organic waste and low cost but also the absence of toxic by-products and the potential for local production in biomass-rich regions — for example, in Kazakhstan’s agricultural areas.

The graphene membranes obtained through this method can be used in various forms — from graphene oxide structures with high hydrophilicity and adjustable permeability to reduced graphene oxide with improved mechanical properties, and even to laminar nanostructures capable of controlling water flow at the nanometer scale. Such membranes are highly selective and can remove up to 99% of salts from water, providing 2–5 times higher efficiency than traditional polymer analogues. In addition, they save up to 30% of energy due to the low pressure required for filtration and possess antibacterial properties that reduce biofouling and extend the service life of water treatment systems.

My research confirms that recycling agricultural waste into high-tech materials can serve not only as a method of utilization but also as a tool for full-scale ecological transformation. By using what was once considered useless — rice husks, crop residues, and other forms of biomass — we gain a unique opportunity to produce next-generation nanomaterials capable of effectively addressing one of the world’s most urgent problems — the shortage of fresh water.

Such materials, particularly graphene membranes, demonstrate outstanding performance in filtration and desalination systems, paving the way for sustainable and affordable water purification technologies.

For Kazakhstan, this concept holds special significance. On the one hand, the country possesses rich agricultural potential and produces tons of biomass annually that can be efficiently processed. On the other hand, in the context of climate change, reduced glacial runoff, and increasing pressure on water management systems, it is crucial to seek local, accessible, and environmentally friendly solutions.

The use of graphene materials derived from agricultural waste can significantly reduce pressure on water resources — especially in the southern regions and densely populated urban areas — while also enabling the development of domestic water purification technologies independent of expensive imports. This provides Kazakhstan with a unique opportunity to act as an exporter of “green” IT solutions that combine the principles of a circular economy, environmental responsibility, and digital efficiency.

Thus, scientific developments in the field of nanotechnology based on local raw materials can become a foundation for sustainable growth — stimulating not only ecological but also economic transformation, from the creation of new industries to the expansion of the country’s export potential in the global green market.

Makpal SEITZHANOVA,

PhD, Acting Associate Professor